Debunking the Myth: Posture, Alignment, and Chronic Pain

- Mia Khalil

- Aug 11, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 12, 2025

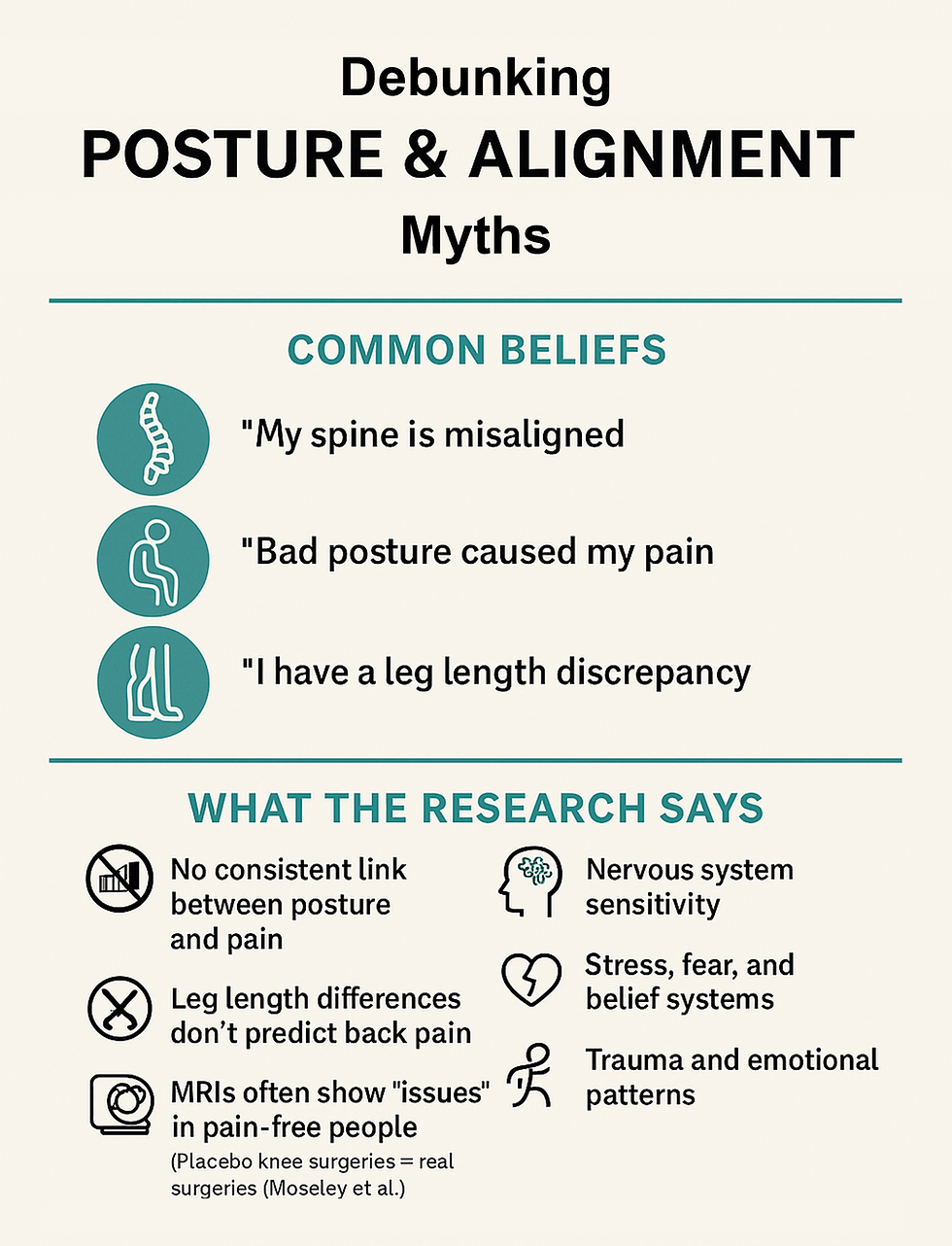

When someone says, “My back is out of alignment,” or “My pelvis is rotated,” they’re often echoing long-held beliefs rooted in the outdated structuralist model of pain. According to this model, factors such as poor posture, pelvic tilt, leg length discrepancies, or spinal misalignments are seen as root causes of pain. But what if science tells a very different story?

Let’s explore what the evidence says about posture, alignment, and chronic pain—and why it’s time to shift from a structure-focused approach to a more holistic, neuroscience-informed perspective.

What Is Structuralism?

Structuralism is the overemphasis on physical “imperfections” like spinal curves, tilted pelvises, or leg length discrepancies as primary causes of pain. While these factors can matter in specific contexts, research shows they are not the driving force behind most chronic pain. In fact, many structural variations are common in people with no pain at all.

A comprehensive article by Paul Ingraham on Structuralism calls these “biomechanical bogeymen” and highlights numerous studies debunking this outdated perspective.

What Does Science Say About Posture, Alignment, and Chronic Pain?

Let’s take a closer look at what the research reveals:

1. Back Pain and Alignment

A seminal study by Lederman (2011) entitled “The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in manual and physical therapies: exemplified by lower back pain” challenges the postural-structural-biomechanical model and concludes that posture is not predictive of back pain.

Swain et al. (2020) found no consensus on the relationship between spinal posture and low back pain across numerous systematic reviews.

In the paper “How do we stand? Variations during repeated standing phases of asymptomatic subjects and low back pain patients”, Schmidt et al. (2018) observed high variability in standing posture among both healthy individuals and those with low back pain.

2. Neck Curvature

Grob et al. (2007) found no consistent association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain.

Richards et al. (2021) showed that neck posture in adolescence does not reliably predict chronic neck pain later in life.

Earlier research by Gay (1993) also documented that cervical curves vary significantly among healthy people.

3. Leg Length and Pelvic Tilt

A 1980 study in The Lancet (Grundy et al.) found no link between leg length discrepancy and back pain.

Similarly, concerns about "pelvic rotation" or "tilts" are often exaggerated and lack solid evidence connecting them to persistent pain.

4. Knees and Alignment

Hochreiter et al. (2020) demonstrated that healthy knees show a high degree of variability in patellofemoral alignment, without pain.

5. Placebo Surgery and Imaging Studies

In a landmark study, Moseley et al. showed that placebo surgery for knee osteoarthritis was just as effective as the real procedure.

MRIs often reveal structural “abnormalities” in people without pain. Multiple studies confirm this, including those by:

Boden (1990): MRI scans of healthy, pain-free adults revealed a high prevalence of spinal abnormalities, such as herniated discs and degeneration, with no associated symptoms.

Jensen (1994): In asymptomatic people, lumbar spine MRIs frequently showed disc bulges, protrusions, and other changes, demonstrating that these findings are often unrelated to pain.

Weishaupt (1998) emphasizes that many MRI findings represent common degenerative changes that occur with age and are not necessarily the cause of pain in all individuals.

Borenstein (2001) demonstrated, in a seven-year follow-up, that MRI scans were not predictive of the development or duration of low back pain. This study reinforced earlier findings (including a 1994 publication by the same researchers) showing a high prevalence of abnormalities like disc bulges, protrusions, and disc degeneration in asymptomatic individuals, with rates increasing with age.

Why It Matters

Believing that pain is caused by alignment issues or posture not only increases fear, but can also lead to unnecessary treatments—braces, manipulations, surgeries—that don’t address the real problem. Worse, it can make people feel broken when, in fact, their pain is often driven by nervous system sensitivity, not structural damage. As Eyal Lederman puts it: “Therapies based on this model are unlikely to offer long-term solutions.”

So, What Causes Pain?

Modern science points toward a neuroplastic, brain-based model of pain. Pain is a complex output of the nervous system, shaped by our thoughts, emotions, experiences, and yes, sometimes tissue status. But it’s not a simple reflection of structure.

What You Can Do

Educate yourself: Read Paul Ingraham’s article on Posture and his comprehensive review of Structuralism.

Stop fearing your body: Minor asymmetries are normal.

Seek mind-body approaches: Practices like pain reprocessing therapy, somatic tracking, and graded exposure are more effective in reducing chronic pain than structural fixes.

Challenge outdated beliefs: The more we align with science, the more empowered we are to heal.

The belief that pain is caused by poor posture or misalignment is a myth not supported by current evidence. It's time to shift our focus from fixing the structure to soothing the system.

If you're ready to dive deeper, explore the rich list of studies linked above or in the original articles themselves. Let’s replace fear-based narratives with empowerment and outdated models with the truth.

Ready to explore this new paradigm for yourself?

If you are prepared to view your pain from a new perspective and feel truly heard and supported, book a discovery call to explore a science-backed and compassionate approach to healing.

.png)

.png)

Comments